the thylacine project

Thylacines - Gone forever or back from the brink?

“It boils down to the fact that for the marsupial wolf, the sands of time have practically run out. Only a philanthropist really interested in our much-vaunted fauna can stay the remaining grains”.

As the only surviving member of the Thylacinidae family, the Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), is known to be one of the many examples of a species driven to extinction by mainly human factors. As a species endemic to Australia, it once flourished in the mainland approximately 2000 years ago, according to fossil evidence, before becoming confined to the midland plains of Tasmania alone due to extinction in other parts of the country.

Modern-day plans for cloning had just begun to take effect with the turn of the 21st century, with many believing that the thylacine was the ideal candidate for the cloning and eventual revival of an extinct species. However, funding for trials in cloning the thylacine were cut short in 2005 by the Australian Museum, after conflicts with members of staff and the general public that this could be seen as an unethical practice to both the surrogate mother and the cloned animal in favour, posing several issues with advancements in cloning at the time.

But, perhaps the future of cloning is not so far away. With many recent controversies over cloning the once extinct wooly mammoth, who is to say that such a beautiful and iconic Australian creature could not be equally as eligible?

- David Fleay, 1954.

"Benjamin"- the last thylacine died in captivity in 1936

General Facts

Scientific Name: Thylacinus Cynocephalus (meaning "dog-headed pouch-dog)

Common Name(s): Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger, Tasmanian Wolf

Description of Appearance: Early descriptions depict the Thylacine as having a sandy brown to grey dense coat and discernible dark stripes across its back from shoulders to tail. It had a relatively large head for its body size, described as wolf-like, with a stiff tail, short front and hind legs and short, upright ears measuring about 80 mm long. Its jaw was large and strong, and adult males typically grew larger than females. Both male and female Thylacines had a backward-facing pouch, and average litter size was up to four cubs, with the young being dependent on the mother until half-grown.

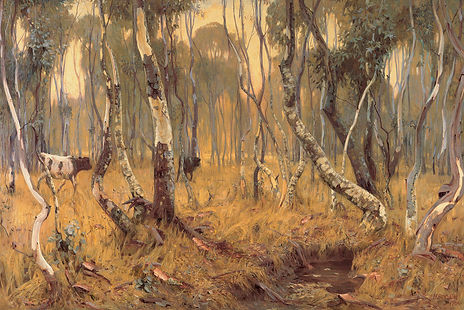

Habitat: Although eucalypt forest proved to be the ideal habitat for thylacines, they were actually known to occupy almost every type of habitat and biome (Flannery 1990a).

Lifespan: Few sources on the lifespan for thylacines leave experts to estimate an average of 5 to 7 years (Tasmanian DPIW 2007), all the way up to 12 to 14 years (Guiler 1985) in the wild. A single living specimen of the thylacine died in London Zoo, aged 8 and a half years, while another specimen died in Beaumaris Zoo, aged 12 years.

Behaviour: Although old texts leave much of the behaviour of the thylacine unknown, it has been described as a social creature that engaged in hunting with groups, and lived with a family. Even though the thylacine was primarily nocturnal, it was observed to move throughout the day, and captive thylacines were often noted to have basked in the sun (Flannery 1990a; Paddle 2000).